Less is More with Social Media - Is Social Media a Contributing Factor in the Rise of Mental Health Issues Amongst iGen Males?

Male suicide and mental health issue rates are rising which has come to define the generation born after 1995; iGen (internet generation). Social media use and mental health issues are the two main factors that differentiate this generation to previous ones. How do young males today use social media?

Originally, there was a major difference between how females used their smartphones (social media and beauty comparison) and how males used their smartphones (video games and pornography). Is this still the case? The following research will strive to answer the question; How do iGen males use social media? Has their use become similar to females or do they still differentiate? As well as this, it will attempt to uncover whether social media is a contributing factor in the rise of iGen male mental health issues and suicide.

Introduction

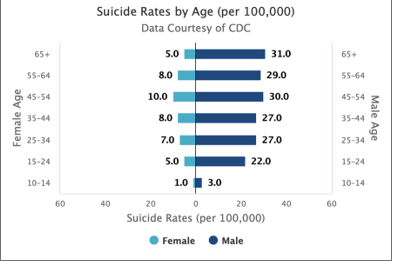

The American Freshman Survey of 2016 saw the number of people suffering from every indicator

of mental health issues reaching all-time highs, with feeling depressed

increasing 95% between 1991 and 2016 (Twenge, 2017a). “Forty-six percent more

15-19-year olds committed suicide in 2015 than in 2007” (Twenge, 2017a) as

shown in Figure one.

“iGen is the first generation that spent (and is now spending) its formative teen years immersed

in the giant social and commercial experiment of social media. What could go

wrong?” (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018)

Figure 1

UK statistics show differences with regards to mental health issues;

“The gap in rates of common mental health problems between young men

and women (aged 16–24) has been growing…in 2014, these symptoms were nearly

three times more common in young women (26.0%) than in men (9.1%)” (Mental

Health Foundation, 2016).

Mental health issues were higher for females than for males in Scotland, shown in Figure two;

Figure 2 – (Mental Health Foundation, 2016)

Suicide amongst young men in Scotland increased for the third consecutive year in 2017 (Samaritans, 2018). Male suicide rates have increased by 1%. Female suicide rate has decreased by 24.3% (Samaritans, 2018).

In the U.S, teens are not going out with friends as much, having less sex, not gaining driver’s licenses and are less rebellious than previous generations (Twenge, 2017a; Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018). In the UK, similar trends have occurred with an 18% drop over 10 years in the number of teens taking driving tests (Usborne, 2017). “Teenage drinking in Scotland has dropped "dramatically” (World Health Organization, 2018; BBC News, 2018). This could be perceived as positive however, if young people are going out less and making less of their own decisions, this could be a contributing factor in a rise of fragility culture resulting in high suicide and depression rates (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018; Twenge, 2017a).

The generation, termed iGen (Twenge, 2017a) will be discussed with other contexts to avoid conflating sociological concepts; cohort, age, and historical period (Kertzer, 1983). The statistics show iGen are more depressed than previous generations were at the same age. The generational differences, such as historical periods lived through, are meaningless to the individual. The variations outlined by average statistics however still show vast differences. To understand a generation, its social and psychological aspects should be examined providing a view of how generations differ. Twenge describes iGen as “born in 1995 or later, they grew up with cell phones, had an Instagram page before they started high school, and do not remember a time before the internet” (Twenge, 2017b). The i stands for internet. Owning a smartphone has become intertwined in this generation’s lives affecting their social habits, mental health and behavior (Twenge, 2017a/b; Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018). “18-year-olds now act like 15-year olds used to, and 13-year olds like 10-year olds. Teens are physically safer than ever, yet they are more mentally vulnerable” (Twenge, 2017b; Thapar et al., 2012). Twenge outlines factors that differentiate iGen from previous generations:

· The extension of childhood into adolescence

· The time spent on the Internet

· The decline of face-to-face interaction

· The rise in mental health issues

· The decline of religious beliefs

· The rise of the concept of safetyism

· Changing attitudes towards work

· The rise of inclusivity and equality considerations

· The rise of independent political views

(Twenge, 2017a)

The research questions being explored are;

RQ1 – How do young males use social media?

RQ2 – What is the state of young males’ mental health?

RQ3 – Does social media contribute to young males’ mental health issues? If so, how?

The hypothesis is that young males would use social media variably, more males would admit to experiencing mental health issues and that social media affects their mental health.

Theory discussed in the literature review explores gender, mental health, social media and identity. Methodology and the results of the research have produced recommendations for further research.

Literature Review

Gender

Studies have shown a positive correlation between smart phone usage and depression rates (Alhassan et al., 2018; Canzian and Musolesi, 2015; Cain, 2018) and that social lives revolve, more so for girls, around inclusion and exclusion (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018; Maccoby, 1999). Young girls use social media more, making their chances of seeing friends doing something without them higher (Twenge, 2017a/b; Statista, 2019b). There is evidence that girls and boys communicate with each other differently. Boys have been proven to be more physically aggressive to hurt others whereas girls are more relationally aggressive attacking another’s social status (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018; Crick and Grotpeter, 1995). Haidt and Lukianoff fail to discuss how social media has changed gender differences in aggressive behavior. They discuss another consequence of gender behavioral difference; beauty ideals.

“It’s not just fashion models whose images are altered nowadays; platforms such as Snapchat and Instagram provide ‘filters’ that girls use to enhance their selfies they pose for and edit, so even their friends now seem more beautiful” (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018).

They fail to discuss male beauty ideals that have risen since the popularization of social media. Females experience higher incidence of mental health issues, however more males act on their mental health issues ending their lives. If there is a direct correlation between the rise of social media use and depression rates, then social media may be a contributing factor in the rise of young male suicides.

“If you imagine all of the kids in America, around 2007 and 2009, you suddenly drop millions and millions of iPhones all over the country and kids pick them up, what are the boys going to do? Video games (and porn [Maher, 2018]) …What the girls are doing is putting something out and waiting anxiously while people comment on it and so it’s the social comparison and the fear of missing out…girls bullying is relational, boys bullying is physical, so social media doesn’t really affect it. But girls can never get away if they’re being bullied” (Haidt, 2018).

This research will scrutinize Haidt and Lukianoff’s work to explore whether their theories are applicable in Scotland.

Mental Health

“Negative views of the self, the world, and the future, as well as recurrent and uncontrollable negative thoughts that often revolve around the self, are debilitating symptoms of depression” and suicidal tendencies (Gotlib and Joormann, 2010). iGen are dealing with the stressors outlined above, contending with social media, beauty comparison, high school grades, university life and bullying. Depression and anxiety disorders will be examined as studies reveal that more than 70% of individuals with depression issues also show symptoms of anxiety (Wu and Fang, 2014; Becker et al., 2013).

Social anxiety can be defined by feelings of apprehension, self-consciousness, and emotional distress when anticipating social-evaluative situations (Leitenberg, 2013). It has been proven that activities such as “media multi-tasking” increases the likelihood of depressive and social anxiety symptoms (Becker et al., 2013) and “the relationship between loneliness and preference for online social interaction is spurious, and that social anxiety is the confounding variable” (Caplan, 2007; Song et al., 2014).

Sociologically, investigations have arisen to determine the causes and consequences of mental illness. Social Stress Theory continues to guide many sociological studies. This perspective states that mental health issues are caused by exposure to social stress, based on social statuses, race/ethnicity, gender, age, earlier life experiences, vulnerability to stress and a limited ability to cope because of low levels of social support, self-esteem, or mastery (Mossakowski, 2014; Aneshensel and Phelan 1999). The statistics reveal “depression has skyrocketed in just a few years, a trend that appears among blacks, whites, and Hispanics, in all regions of the United States, across socioeconomic classes, and in small towns, suburbs and big cities” (Twenge, 2017a). One aspect that has been proven to contribute to rises in mental health issues amongst iGen is parenting.

“Over the past half century, in the United States and other developed nations, children’s free play with other children has declined sharply. Over the same period, anxiety, depression, suicide, feelings of helplessness, and narcissism have increased sharply in children, adolescents, and young adults” (Gray, 2011).

The life of a child is safer now than it has ever been (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018; Malone, 2007). This safetyism, defined as the intense concentration on keeping individuals “safe” from all forms of harm, physical or emotional (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018; Twenge, 2017a), can have a detrimental effect on children’s phycological make-up later in life. Parents are allowing less free-play, in which children play unsupervised, immersed in peer culture; learning from each other and from experience (Speigel, 2008; Carver et al., 2010). Too much close supervision and protection can “morph into safetyism” (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018) taking children who are resilient by nature and turning them into young adults who are fragile due to the restriction of experiential learning in life (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018; Twenge, 2017a/b; Gray, 2011). By allowing children to spend more time using technology, parents are causing, with good intentions, a rise in depression and social anxiety (Twenge, 2017a).

Sociologically, family structure affects how parents raise their children. The most significant divide can be seen by contrasting two types of families; “those in which children are raised by two parents who each have four-year college degrees and are married to each other throughout their children’s childhood, and those in which children are raised by a single or divorced parent (or other relative) who does not have a four-year college degree” (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018). Family structure could be attributed to class as the first type of parent is common amongst the upper third of the socioeconomic spectrum with which marriage rates are high and divorce rates are low (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018; Lareau, 2011; Putnam, 2015). These parents generally employ a parenting style Lareau defines as “concerted cultivation” (Lareau, 2011; Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018), defined as parents filling their children’s calendars with adult-guided activities, lessons and experiences. They monitor their children’s school ability (Lareau, 2011; Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018). The second type of family is common among the bottom third of the socioeconomic spectrum, these parents generally employ the style Lareau defines as “natural growth parenting” (Lareau, 2011; Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018) in which children experience “long stretches of leisure time, child-initiated play, clear boundaries between adults and children, and daily interactions with kin” (Lareau, 2011). The differences between these two types of socioeconomic classes include the working-class children experiencing adversity such as divorced parents, lack of food, clothes or care from family etc. (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018). “Severe and chronic stress…can disrupt the basic executive functions that govern how various parts of the brain work together to address challenge…” (Putnam, 2015). Attributes of typical working-class parenting and family structure may be a contributing factor increasing the likelihood of mental health issues for their children in adulthood. The other style used primarily by middle to upper class parents deny their children the “small challenges, risks, and adversities that they need to face on their own in order to become strong and resilient adults” (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018).

Social Media

In 2010, Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger introduced Instagram (Brown, 2018; Evans, 2018), a social networking site for individuals to post pictures and share content with others while “following” them as well (Gallegos, 2018). Following others is the act of subscribing to someone else’s posting patterns (Gallegos, 2018; Desreumaux, 2014). Now, “Instagram has over 150 million users, 16 billion photos shared, 1.2 billion “likes” every day, and 55 million photos posted per day” (Gallegos, 2018; Desreumaux, 2014). Instagram users and their posts will be discussed in this research to gain an understanding of how young males use Instagram, how they feel about their usage and how they form their online identities.

Social media has built online spaces where the economy and social life can unfold. Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

“…do media on a mass scale, but through a very different spatial configuration from that of classic mass media. Instead of distributing the same content out to “everyone” … they provide online “platforms” (Gillespie, 2014) where “anyone” can interact with anyone else” (Couldry and van Dijck, 2015).

The automated mechanisms stemming from these connective platforms now dictate how online sociality is designed (Couldry and van Dijck, 2015). Facebook and Instagram’s “friending” or “liking” buttons have little significance in the social reality of making friendships or preferring cultural content (Gerlitz & Helmond, 2013); they are computational systems that assign data their value as economic currency in a global online sociality (Couldry and van Dijck, 2015). The ‘sociality’ of social media interaction does not reflect the sociality of “real life” so it can be assumed that the increase of social media use affects how iGen communicates in “real life.”

This economic currency can be regarded as social capital, defined as “the value derived from resources embedded in social ties with others” (Lin, 2008; Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2017). Used to define structures of opportunity and action in communities, later adapted to studies of individual behavior towards policies and the public sphere, then shifted from communities defined by geo-spatial structure to one defined by the structure of interpersonal relationships (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2017; Coleman, 1998, 1990; Bourdieu, 1985; Lin, 2001; Brehm and Rahn, 1997; Fischer, 1982; Rainie and Wellmann, 2012). As academics began to view communities as diffused networks of personal relationships, they came to see social capital as the value these relationships add to individuals’ lives (Burt 2005; Shah and Gil de Zúñiga, 2008; Gil de Zúñiga, 2017). Social capital created on social media sites differs from social capital created offline (Gil de Zúñiga, 2017). Social media has altered the structure of communication through weak-tie relationships (Gil de Zúñiga and Valenzuela, 2011), meaning it has provided individuals with different kinds of social information or data about relationships (Gil de Zúñiga, 2017; Kwon et al., 2014; Walther et al., 2008) in which value can be produced (Gil de Zúñiga, 2017; Ellison et al., 2011). “The latent distribution of social value and resources, the process of recognition and development of these very characteristics, as well as the conversion of these values and resources into more tangible individual or collective benefit” (Gil de Zúñiga, 2017) make social media social capital different to offline social capital. The values of social capital could vary from relationships, connections and communities. Social capital signals the development of sound interpersonal relations with users and a reputation that holds the social media user in “a position where the information they share is meaningful, timely and will impact their significant number of followers” (Recuero et al., 2011; Goodyear et al., 2014). The user may hold social capital through interpersonal relations, reputation through number of followers and knowledge that what they share (i.e. images) is meaningful through the number of likes gained. This reputation is aligned with how the user presents themselves to their followers to gain social capital, likes and confirmation.

Theories of Identity

Erving Goffman compares presenting one’s identity to that of playing a part in a play. An individual “plays a part” when he invites his observers to perceive the impression that is portrayed. The audience are invited to observe that the “character” they see inherits the attributes they seem to possess (Goffman, 1956).

“At one extreme, we find that the performer can be fully taken in by his own act…when his audience is also convinced in this way about the show he puts on—and this seems to be the typical case —then for the moment, anyway, only the sociologist or the socially disgruntled will have any doubts about the 'realness’ of what is presented (Goffman, 1956).

The typical social media user may be convinced that the identity they share online is the reality of their life, just as their audience perceive them. Only when we peek behind the curtain, we see behind the scenes of a social media user’s ‘real reality.’ The perceived reality posted on their social media account are their best selves. By only posting interesting factors of their lives, the audience and themselves perceive their life to be more interesting than their reality of perhaps, a 9-5 office job, confirming Goffman’s concept of impressions with the use of a metaphorical mask, meaning an individual can bring forward certain aspects of their lives whilst marginalizing others (Goffman, 1956).

“The distance between performer and audience that physical detachment provides makes it easy to conceal aspects of the offline self and embellish the online” (Bullingham and Vasconcelos, 2013). This can be related to the “spitting character” of the self-whilst interacting, in which the self is divided (Goffman, 1971).

It could be considered that Goffman’s concepts are outdated for today’s digital society (Arundale 2010). Other academics deem online spaces as an extension of Goffman’s theories (Miller, 1995). It seems that the offline, face-to-face interactions are the “real thing” however, the customizable and personal online profiles are perhaps the most intricate means of identity management (Jenkins, 2010). Users of social media create metaphorical masks to portray the best versions of themselves then behind the scenes preparations for their online selves occurs.

Charles Cooley’s Looking Glass Self (LGT) theory presents the idea of a self from three main principles; “the imagination of our appearance to the other person; the imagination of his [sic] judgment of that appearance, and some sort of self-feeling, such as pride or mortification” (Cooley, 1922). Our view of who we are is dependent on how others view us, and we learn by interpreting this (Cooley, 1922; Zhao, 2005). We accomplish this through an array of verbal and non-verbal cues such as gestures and facial expressions (Zhao, 2005). Online spaces have made it harder to apply Cooley’s LGT to social media users. The use of likes and retweets perhaps allow the user to define other’s judgement of their online personalities. Cooley’s LGT can be applicable to social media use however, the idea that individuals view themselves with regards to how others view them through face-to-face interaction cannot be applied to social media use.

New Communication Technology (NCT) was believed to weaken the connections between physical and social "place." NCTs mesh public and private, beckon new types of performances, and form new collective configurations (Meyrowitz, 1985, 1989 and 1997; Cerulo, 1997). The introduction of new communicational modes and new ways of selecting and sharing information means NCTs create new environments for self- development and identification (Cerulo, 1997; Altheide 1995). George Herbert Mead discussed agency, in terms of the Self, which is social and cognitive, in that it develops when interaction with others occurs (Warburton and Hatzipanagos, 2013; Aboulafia, 2009). These groups of individuals with a critical influence on the construction of the Self can be termed the “generalized other.” (Warburton and Hatzipanagos, 2013). Individual’s identities are adaptable, to understand an individual’s identity, comparisons between the individuals, the context of interaction, their intentions and their “generalized other” should be considered (Warburton and Hatzipangos, 2013; Jenkins, 2004). The social media user must be examined while their profile, the intentions behind activity such as posting and other users they interact with should be examined to explore the identity of an individual social media user.

Communication Theory of Identity (CTI) discusses how identity is formed. Identity formation is internally and socially constructed, indicating communication is a factor when discussing an individuals’ identity. Many sectors of experience construct an individual’s identity such as cognition and communication which are constructed in “intrapersonal and interpersonal” manners (Hecht, 1993; Gallegos, 2018). Hecht’s concepts of identity can be related to masculinity (Gallegos, 2018). The different forms of masculinity are emphasized and deemphasized based on culture, location, and circumstance, in the same way that identity is expressed (Gallegos, 2018). Identity gaps are another significant factor as individuals rarely express their true feelings for fear of interacting outside social norms (Gallegos, 2018; Jung and Hecht, 2004). “The disconnect between what is said and what is shown is an example of an identity gap” (Gallegos, 2018). Identity gaps can be attributed to social media use, as an audience may interpret the intentions of a user’s post, however the user may have had different intentions, making social media analysis difficult due to its subjectivity. In-depth interviews may only show one side of a user’s habits and posts whereas an Instagram scrape may portray another side.

Identity Theory plays its part taking fragments from sociology, psychology, psychoanalysis, communications, political science and history (Stryker & Burke, 2000; Gallegos, 2018). It combines theories to provide a definition of identity with the use of self-verification theory, symbolic interactionism, self-reference theory and self-categorization theory (Stryker and Burke, 2000; Gallegos, 2018), combining ideas into one that incorporates two principles: identity formed through social structures and its influences on social behavior, and the internal dynamics of self-processes influencing social behavior (Stryker and Burke, 2000; Gallegos, 2018). Identity is formed by the surrounding society in which one lives and the internal dialogue and proceeding actions that one follows (Gallegos, 2018). Social structures are part of the society in which an individual presents their identity, within these social structures, the majority provide the behavior and identity construction norms for individuals to follow, like typical male actions are followed and aligned by the majority (Gallegos, 2018).

The concept of masculinity can be aligned to three sub-categories for the purposes of analysis: traits, ideology and hegemonic masculinity (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Pleck, Sonenstein, Ku, 2004; Gallegos, 2018). Hegemonic masculinity can be defined as the pressures afflicting males, ideology being more precise and traits regarding the physical, emotional and psychological characteristics males can hold (Gallegos, 2018). “All three, moreover, are related to identity because to be a “man” in society means adhering to or negotiating what it means to be male and how to properly express manliness” (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Gallegos, 2018). The concept of masculinity is difficult to define as the subjectivity of the term is prevalent. What masculinity means in one country or culture may be different to another’s. This is evident on social media as different cultures post what masculinity means to them based on the focus of the image, for instance being at the gym. Hegemonic masculinity is thought of as an expectation to perform (Goffman, 1956) based on the context and situation, what it takes to be a man and how to act to adhere to this (Gallegos, 2018). The term has been used to inflict pressures on males to think in terms of typical masculinity and manliness. The media can contribute to how males should consider what it means to be a man; sports stars, celebrities, reality TV stars and other social media users can influence how males view manliness and how they act, dress and speak (Gallegos, 2018; Waling, 2016).

Performativity can be regarded as a contribution to understand how males present themselves offline and online; “Performativity, then, is identity produced through the citation of culturally given identity categories or norms in a reiterative process and occurs across both offline and online interactions” (Cover, 2012). If an individual adheres to social media norms such as posting an image of themselves at the gym, they can feel more confident as part of the male social media social structure. Individuals can see confirmation of this fitting in with the use of likes (Gallegos, 2018; Chua and Chang, 2016). Sharing posts, phrases, or joining groups online is partly personal and a way for others to see what an individual is doing, furthering their cultivated identity online (Gallegos, 2018). If these actions online are not met with confirmation through likes or retweets, then it is likely that the individual may disregard the notion of identity they followed in certain posts to be accepted. Whilst focusing on the confirmation or not an individual may receive after posting, it must be acknowledged that “solely focusing on social media recognition is a trap because while identity is formed through recognition, the constant awareness of people viewing one’s online presence can result in negative outcomes” (Gallegos, 2018; Ong et al., 2011). A male feels the need to post an image of themselves at the gym to feel acknowledged and ‘seen’ to establish themselves and their identity as validated and recognized (Gallegos, 2018; Xinaris 2016). Instead of gaining simply confidence and confirmation, social media use can result in an “unreal representation of the self” (Gallegos, 2018). It becomes easier to understand why more young males have mental health issues and suicidal tendencies. They may continue to post on social media to adhere to masculine expectations which could result in a false-self, which may lead to pressure to continue this identity offline. This could be too much for a young male to handle mentally.

Methodology

This research utilized two research techniques; in-depth interviews and visual content analysis. This would portray the habits of males on social media, through asking the source questions.

Ethics

Ethical approval was achieved through the University ethical approval form, then approved by the research supervisor. Issues regarding “copyright, creativity, transformative works, fair use, and fair dealing are seemingly an inescapable part of the circulation of visual material online” (Highfield and Lever, 2016; Lessig, 2005, 2008; Meese, 2014). The intended participants were over eighteen years old and verbal consent was achieved and recorded regarding participation and the use of data provided faces were blurred and usernames were not presented.

The researcher has experience working with clients experiencing mental health issues. Questions were asked regarding participants’ mental health, these were two closed questions and one open-ended question allowing the participant to reveal as much or as little as he chose. Participants were assured that they had the freedom to withdraw at any time. The researcher interviewed friends and strangers.

Any images with individuals under the age of eighteen were not used, images in which the subject could include incriminating features were not used to ensure reputation protection and any other identifiable information was blurred or not included. Names were exchanged for anonymity.

Case Study

A case can be described as an event, an entity, an individual, a unit of analysis or a group of individuals (Noor, 2008; Gallegos, 2018). The issue was male mental health, social media habits and the possible correlation of the two in which each interviewee was a single case as case studies should not be intended to examine an entire organization, rather a particular issue (Noor, 2008). Case studies are concerned with how and why things happen, which allows the exploration to determine differences, habits and information through the interviews (Noor, 2008; Anderson, 1993). The researcher was able to examine the processes of real-life activities of young males through multiple sources; visual data and spoken words (Noor, 2008; Gallegos, 2018). Case studies are useful when the researcher is attempting to understand particular issues in great depth, in order to explore rich data (Noor, 2008; Patton, 1987; Gallegos, 2018).

It is difficult to generalize a few interviews to a whole population; however, it does produce a varied picture of the issue, and gives the researcher a rich view of the data compared to using a survey for example in which the answers are not likely to be as rich (Noor, 2008). Case studies allow generalizations to an extent, in that the findings of multiple cases can lead to some form of replication (Noor, 2008).

The researcher undertook a collective/multiple case study (Baxter and Jack, 2008; Gallegos, 2018; Yin, 2003; Baxter and Jack, 2008) which allows the researcher to examine differences between cases, in which the goal is to replicate findings across cases so that comparisons can be drawn (Yin, 2003; Baxter and Jack, 2008). In this case, comparisons would be drawn between each participant’s answers and Instagram posts.

In-Depth Interviews

In-depth interviews are conducted one-on-one, use open-ending questioning and inductive probing to gain depth and feel like a conversation (Guest et al., 2013). By having the interview one-on-one, the researcher is able to focus on what is being said whilst exploring tone, body language, content and how the interviewee views their context (Guest et al., 2013; della Porta, 2014). The researcher utilized open-ended questions (Appendix 1). Any planned questions are designed to lead the conversation to the topic of study and flesh out any information provided (Guest et al., 2013; della Porta, 2014; Weiss, 1994). Inductive probing is asking questions that are based on the interviewee’s responses that are linked to the topic of study (Guest et al., 2013; della Porta, 2014, Weiss, 1994; Holstein et al., 2002). In-depth interviews should be made to feel like a conversation making it almost seem “deceptively simple to the outside observer” (Guest et al., 2013; della Porta, 2013; Weiss, 1994).

They allow the researcher to gain rich data from experts on the issue. They are simple to conduct as a conversation or interview is usually familiar to everyone and asking probing questions regarding sensitive topics can seem more daunting to an individual in a group setting as opposed to a one-on-one interview (Guest et al., 2013). In-depth interviews provide information from the source of the images so that the researcher can be certain about intentions regarding images. Problems with in-depth interviews can arise when the interviewees “do not want to, and do not have to, reveal everything about themselves” (Charmaz, 1995; Nunkoosing, 2005), they can choose the aspects of his or her life that he or she is most interested in sharing (Nunkoosing, 2005). Further, the interviews were carried out by phone, so this presents further issues such as lack of facial expression or hand gestures.

Visual analysis

Visual content is a critical component of social media, on platforms framed around the visual (Highfield and Leaver, 2016). The visual content shared on Instagram can be one of the principle devices for experiencing something, for giving an appearance of participation, therefore if you did not take a photograph and share it, you did not do it (Sontag, 2005; Highfield and Leaver, 2016). The visual is a means for presenting online identities, through profile pictures, everyday snapshots and created and curated media (Highfield and Leaver, 2016; Miller, 2015; Blackwell et al., 2014).

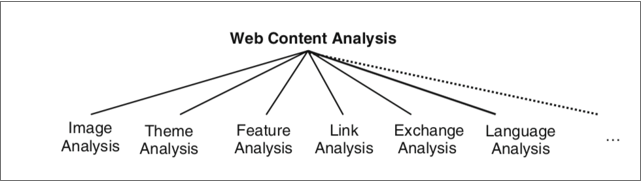

Figure three illustrates the separate components of web content analysis. Image analysis is included because even though image content can be explored for its themes and features, the interpretation of visual content can benefit from methods drawn from iconography and semiotics, which are not included in any other component (Herring et al., 2010).

Figure 3 (Herring et al., 2010)

Intent are portrayed by levels of visual and textual content on social media, exposing the digital and cultural literacies of users and the tropes, affordances, and practices apparent on different platforms (Highfield and Lever, 2016; Boczkowski, Matassi and Mitchelstein, 2018). The researcher analyzed how images are perceived then explored how they were intended from the source of the images.

“The visual adds levels of trickiness to such analyses: first in accessing the images, videos, or other linked and embedded files, and then in studying them, which requires more individual intervention and interpretation…” (Highfield and Leaver, 2016).

Accessing the images revealed little friction due to gaining consent for access and exploration of the images. Difficulties arise when exploring the images themselves as it can be awkward to perceive intent behind the images and the perceived reaction of the user from the audience.

Population

The population consisted of seven participants, all males born after 1995. All were white, predominately middle-class individuals and heterosexual. Three were known to the researcher and four were not.

Sampling

Snowball sampling “yields a study sample through referrals made among people who share or know of others who possess some characteristics that are of research interest” (Biernacki and Waldorf, 1981; Noy, 2008). It is easier to gain participants who were friends and work colleagues to start with, then gain referrals from participants unknown to the researcher producing a sample of friends, colleagues and strangers.

The size of the sample is fixed and determined before sampling begins and is effective when the focus or part of the study is on a sensitive issue, possibly concerning a private matter which requires the knowledge of insiders to locate people for study (Biernacki and Waldorf, 1981; Goodman, 1961).

Finding participants and starting referral chains (Biernacki and Waldorf, 1981) was one issue, however as the initial interviewees were known to the researcher, this made it easier, although snowball samples will be biased due to the inclusion of individuals with interrelationships and will overemphasize interrelated social networks (Griffiths et al, 1993; Atkinson and Flint, 2011). Verification of eligibility and selection bias (Biernacki and Waldorf, 1981; Atkinson and Flint, 2011) are issues in which the researcher must verify the eligibility and nature of the respondents and control the limited scope of the participants. This was achieved through the verification of the Instagram accounts and verification of age through Facebook profiles for those unknown to the researcher and maintaining that the participants chosen were from a variety of workplaces, universities or backgrounds.

Transferability/Dependability

Transferability relates to the ability of the findings to transfer to other settings (Gallegos, 2018). It is a concept used to partially generalize results, however due to the subjectivity of this research, it cannot be fully generalized (Gallegos, 2018). These findings could influence further research as this study mainly used participants from middle class backgrounds. Future research could focus on a more socio economic and cultural mix. This paper ensured transferability by stating the nature of the participants used in the research, contextual background information and demographics (Gallegos, 2018; Noyce et al., 2011).

Dependability regards the ability for this research to be replicated in the future meaning the methods used and how they were carried should be clear (Gallegos, 2018). Weaknesses of methods used and how they were carried out should be stated to better further research on similar subjects (Gallegos, 2018; Krefting, 1990).

Conclusion/Discussion

From the Interviews and Graphs

The results seem to confirm the statistics given in the introduction; male mental health issues are rising (Samaritans, 2018; Mental Health Foundation, 2016) as the majority of participants said they had had a depressive episode in the last year. More people are willing to speak about mental health which could result in more people admitting to having mental health issues. Or it could result in more people self-diagnosing themselves when perhaps, what they were experiencing was not necessarily a mental health issue. This could be an example of an identity gap as it may be a social norm to say you have had a mental health issue so the participants may have responded to these questions with the fear of acting outside the social norm (Gallegos, 2018; Jung and Hecht, 2004). Whatever the case, the results from the mental health questions in this research portrays many males feel they have had a depressive episode. This appears to answer research question two.

Perhaps then, it can be suggested that the answer to research question three is yes, social media does affect young males’ mental health. The majority of respondents said social media affected their mental health for the worse, however some outlined positive aspects. A positive aspect was the comfort felt on social media if the situation of poor mental health arose or the number of friends or followers on social media suggest aspects of support for the user. Young males tend to notice the effects of social media on their mental health in terms of activity. Noticing someone on social media partaking in something fun or exciting while they are sitting in their house or at work affects their mental health. One respondent said they feel worse the more they are on social media exposing social media’s effect on young males’ mental health. The majority of participants failed to mention how social media affects their mental health based on how they look in comparison to others which either shows that young males differ from females or that young males tend not to admit to these comparisons. Either way, social media seems to contribute to young male’s mental health for the worse.

How males view masculinity was another aspect explored in the interviews. Young males find this question difficult to answer. Most of the males focused on the traits of masculinity rather than ideology or the pressures inflicted upon them (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Pleck, Sonenstein, Ku, 2004; Gallegos, 2018). A common theme that emerged was strength which does appear in many definitions. Some participants focused on traditional connotations of the word such as providing for a family, facial hair or a heterosexual orientation. Others focused on how males behave, how one views themselves and their outlook. Being a male, according to some participants, is being self-assured with one’s actions and thoughts, being proactive and positive. Others concluded that masculinity is an idea of how males should behave and look rather than definitively how males should behave and look which is encouraging for males who perhaps do not fit these characteristics as it is only an idea rather than a requirement. These do not seem to be conflicting responses as the majority focus on positive aspects, however, some focus on aspects that could suggest that males who do not fit the traditional persona of being masculine are not masculine. Sections of society like the LBGTQ+ groups, males without beards, males experiencing mental health issues who perhaps do not have a positive outlook or males without partners may feel marginalized, so work should be done to aid in discussing masculinity with young males to avoid unintentional discrimination.

Based on how the participants responded to questions regarding their first time drinking alcohol or using a recreational drug, it can be stated that young males still went out in their teenage years, made their own choices to use alcohol and took a risk to an extent using a recreational drug which suggests that iGen males do make independent choices which may indicate that declines in alcohol consumption and socializing is not a significant contributing factor to mental health issues as this research found little decline or increase in these areas.

Other factors that were considered such as class and parenting styles did not portray any significant differences as the majority of respondents were middle class and the majority of participants had a depressive episode in the last year regardless of class or whether they grew up in a two-parent household or the age they were first allowed out with friends unsupervised. Therefore this should not be considered as a contributing factor for mental health issues, based on this research, however further research would be beneficial.

From the Visual Analysis

Young males mainly post on social media when they partake in something interesting such as a day out, a concert or a holiday so young males do not post on Instagram in a realistic manner as they fail to post more mundane aspects of their lives such as their home life etc. The participants present themselves as interesting and always involved in interesting activities or travels, so their audience may perceive this as they do; that must be their real life (Goffman, 1956). Most of the images examined featured the participants in the posts so there could be aspects of self-presentation in that they post attractive images of themselves, whether that be pictures of them smiling or dressed up. This is evidence of self-presentation as they mainly present attractive images of themselves to portray good-looking or happy individuals whereas behind closed doors, as purported by the mental health questions, this is not always the case.

The participants mostly ignored the fact that they were in the images and focused on the activity or the place they were to present themselves as interesting. The majority failed to mention their appearance in the posts which, it can be assumed, was an aspect of their intentions before posting an image. Reasons such as success, comedy or interest were responses to what they wanted to portray. Few respondents divulged that appearance did play a role in their posting habits, stating that they wanted to look good or handsome in images portraying perhaps males do consider their appearance when posting images but only some are aware of it or will admit to it. Appearance was seldom mentioned which is a major aspect of posting on social media revealing young males use social media mostly to portray themselves as interesting in what they do rather than how they look but that does not mean that appearance is not a factor for young males, this only portrays how they view their posting habits. Young males tend to ignore appearance-based intentions even though, it can be assumed, this was a factor or intention when posting some images such as of themselves.

It seems the researcher’s hypothesis was generally correct. More young males did admit to having mental health issues than didn’t and most of the participants admitted that social media affects their mental health for the worse. Some males do use social media more often than others. Young males do use and view their social media use similarly. Most of the participants use social media but do not post very often and most participants compare themselves to other social media users in terms of what they are doing as opposed to how they look. They post images with the idea of what they are doing being more significant than how they look, or so they say, this could be perceived as more males will not admit or are not aware of the appearance aspects of posting images of themselves on Instagram.

Recommendations

There are aspects of this research that can be replicated. Some aspects should be acknowledged which could be perceived as weaknesses to improve further research in this area.

Some participants were known to the researcher. This could be identified as positive as perhaps divulging sensitive aspects of the participant’s lives to a known voice would be more comforting and therefore more information could be obtained. Or, perhaps as the participants are known to the researcher, they would not feel comfortable divulging sensitive information for fear of judgement or criticism. If this research were scheduled at a time when the ideal participant group were all in one place i.e. university, participants not known to the researcher would be easier to obtain. Snowball sampling techniques meant the respondents were similar to that of the researcher’s friends and the researcher himself making it difficult to generalize the results to other parts of Scottish iGen males.

The majority of participants were from middle class backgrounds making this research somewhat one-dimensional. All respondents were white and heterosexual. With more time, the researcher would have more freedom to focus on obtaining a more diverse group of participants representative of Scottish society. The subjectivity aspects of this research make it difficult to generalize the results to the whole society of iGen Scottish males however, the research was comprehensive resulting in it being easier to replicate.

Further research could focus on a wider range of social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter and could focus on more than just the images themselves; tweets, captions or status updates could be analyzed.

Ethical concerns were evident to the researcher regarding mental health, so little was asked regarding this. With the knowledge of more ethical freedom, more intimate questions could be asked regarding topics such as suicide as this is the primary concern of male mental health issues in Scotland.

In terms of the interviewing process, having the questions in comprehensive order would make it easier to transcribe and analyze when writing the results sections. The researcher had to transcribe one answer then write another section due to the somewhat disorganized nature of the interview questions written. Interviewing the majority of respondents by phone has limitations such as being unable to read the respondents facial expressions or hand gestures which would add more depth to responses. Having all interviews conducted face to face would enhance results.

To address the issue of masculinity, changes in educational establishments should be made to inform young males about masculinity and the possible dangers of social media to reduce harm and contributions should be made to encourage further research in this area to gain a wider picture of the issues affecting young Scottish males today to combat future issues as “it is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men” (Douglas, n.d.; Edelman, 2009). Further research should also be conducted regarding cultural differences of male behavior to perhaps inform healthy ways to interact and behave. For parents and people involved in raising young people, “prepare the child for the road, not the road for the child” (Haidt and Lukianoff, 2018).

This research has confirmed that iGen males experience mental health issues and that iGen males use social media, they feel, too much and compare themselves to celebrities and friends, however not as much as females do. It has revealed that Haidt and Maher’s statement that iGen males only use their smartphones for video games and pornography is outdated as this research shows iGen males use social media very frequently to the point that it has a damaging effect on their mental health. Although females still use social media more than males (Twenge, 2017a/b; Statista, 2019b), compare themselves to other friends more and statistics show female mental health issues are rising at a higher rate than males, iGen males are catching up. The main finding is that iGen males say they compare themselves to other friends in what they do rather that how they look and state their intentions for posting images in this way, portraying differing behaviors in males and females.

There is gender differentiation in suicide rates among iGen and this research has shown that social media is likely to be a contributing factor in male mental health issues so unless males follow the advice of Connor; “Less is more for your mental health,” then male suicide rates may continue to rise to more endemic levels.

Bibliography

Aboulafia, M. (2009). George Herbet Mead. In E. N Zalta (Ed.), Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (2009 Summer ed.) Stanford, CA: The Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Addis, M.E., Truax, P., & Jacobson, N.S. (1995). Why do people think they are depressed?: The Reasons for Depression Questionnaire. Psychotherapy, 32.

Akiskal H. S. (1998) Toward a definition of generalized anxiety disorder as an anxious temperament type Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998: 98 (Suppl. 393): 66 73. 0 Munksgaard 1998.

Alhassan, A., Alqadhib, E., Taha, N., Alahmari, R., Salam, M. and Almutairi, A. (2018). The relationship between addiction to smartphone usage and depression among adults: a cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1).

Altheide DL. (1995). An Ecology of Communication: Cultural Formats of Control. Hawthorne: Aldine de Gruyter

Aneshensel, Carol S., and Jo C. Phelan, eds. (1999). Handbook of the sociology of mental health. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Arundale R (2010). Face as emergent in interpersonal communication: An alternative to Goffman. In: Bargiela-chiappini F, Haugh M (eds) Face, communication and social interaction. London: Equinox

Atkinson, D.R., Worthington, R.L., Dana, D.M., & Good, G.E. (1991). Etiology beliefs, preferences for counseling orientations, and counseling effectiveness. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38.

Atkinson, R. and Flint, J. (2011). Accessing Hidden and Hard-to-Reach Populations: Snowball Research Strategies. University of Surrey, [online] (33). Available at: http://citizenresearchnetwork.pbworks.com/f/accessing%2Bhard%2Bto%2Breach%2Bpopulations%2Bfor%2Bresearch.doc [Accessed 8 Jul. 2019].

BBC News. (2018). 'Dramatic' drop in teenage drinking. [online] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-45645295 [Accessed 20 May 2019].

Becker, M, Alzahabi, R, and Hopwood, C. (2013) Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking.tp://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0291

Biernacki, P. and Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball Sampling: Problems and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling. Sociological Methods & Research, 10(2).

Blackwell, C., Birnholtz, J., & Abbott, C. (2014). Seeing and being seen: Co-situation and impression formation using Grindr, a location-aware gay dating app. New Media & Society. doi:10.1177/1461444814521595

Boczkowski, P., Matassi, M. and Mitchelstein, E. (2018). How Young Users Deal With Multiple Platforms: The Role of Meaning-Making in Social Media Repertoires. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(5).

Booth, R. (2019). Anxiety on rise among the young in social media age. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/feb/05/youth-unhappiness-uk-doubles-in-past-10-years [Accessed 21 May 2019].

Bourdieu, P. (1985). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education New York, NY: Greenwood.

Brehm, J., & Rahn, W. (1997). Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. American Journal of Political Science, 41(3). doi:10.2307/2111684

Brown, A. (2018). Kevin Systrom In His Own Words: How Instagram Was Founded And Became The World's Favorite Social Media App. [online] Forbes.com. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/abrambrown/2018/09/25/kevin-systrom-in-his-own-words-how--instagram-was-founded-and-became-the-worlds-favorite-social-media-app/#459390a542bf [Accessed 22 May 2019].

Brown, C., Dunbar-Jacob, J., Palenchar, D.R., Kelleher, K.J., Bruehlman, R.D., Sereika, S., et al. (2001). Primary care patients’ personal illness models for depression: A preliminary investigation. Family Practice, 18.

Brügger, N. (2015). A brief history of Facebook as a media text: The development of an empty structure. [online] Firstmonday.org. Available at: https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/5423/4466 [Accessed 22 May 2019].

Bullingham, L., & Vasconcelos, A. C. (2013). ‘The presentation of self in the online world’: Goffman and the study of online identities. Journal of Information Science, 39(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551512470051

Burt, R. S. (2005). Brokerage and closure: An introduction to social capital. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Cain, J. (2018). It’s Time to Confront Student Mental Health Issues Associated with Smartphones and Social Media. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education: Volume 82, Issue 7, Article 6862.

Caplan, S (2007) .CyberPsychology & Behavior.Apr 2007.ahead of printhttp://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9963

Canzian, L. and Musolesi, M. (2015). Trajectories of depression: unobtrusive monitoring of depressive states by means of smartphone mobility traces analysis. Proceedings of the 2015 ACM

Carver, A., Timperio, A., Hesketh, K. and Crawford, D. (2010). Are children and adolescents less active if parents restrict their physical activity and active transport due to perceived risk?. Social Science & Medicine, 70(11).

Charmaz, K. (1995). Between positivism and postmodernism: Implications for methods. Studies in Symbolic Interaction, 17.

Chua, T. and Chang, L. (2016). Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 55.

Evans, G. (2018). The dog that launched a social media giant. [online] BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-45640386 [Accessed 22 May 2019].

Foulks, E.F., Persons, J.B., & Merkel, R.L. (1986). The effect of patients’ beliefs about their illnesses on compliance in psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 143.

International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing. [online] Available at: https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2750858.2805845 [Accessed 20 May 2019].

Center for Collegiate Mental Health. (2017). 2016 Annual Report (Publication No. STA 17-74).

Cerulo, K. (1997). Identity Construction: New Issues, New Directions. Annual Review of Sociology, 23(1).

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. doi:10.1086/228943

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Connell, R., & Messerschmidt, J. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19 (6),

Cooley, Charles H. 1922. Human Nature and the Social Order. New York: Scribner’s

Couldry, N. and van Dijck, J. (2015). Researching Social Media as if the Social Mattered. Social Media + Society, 1(2), p.205630511560417.

Cover, R. (2012). Performing and undoing identity online: Social networking, identity theories and the incompatibility of online profiles and friendship regimes. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 18(2).

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational Aggression, Gender, and Social-Psychological Adjustment. Child Development, 66. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1131945

Desreumaux, G. (2014). The complete history of Instagram. We Are Social Media. Retrieved from http://wersm.com/the-complete-history-of-instagram/#prettyPhoto

Dictionary.com. (2018). What Does flex Mean? | Slang by Dictionary.com. [online] Available at: https://www.dictionary.com/e/slang/flex/ [Accessed 22 Jul. 2019].

Edwards, E. and Fox, M. (2018). Teens would rather text than talk to you, survey finds. [online] NBC News. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/more-teens-addicted-

Douglas (n.d.) cited in Edelman, M. (2009). The Cradle to Prison Pipeline: America’s New Apartheid. HARVARD JOURNAL OF AFRICAN AMERICAN PUBLIC POLICY, [online] 15. Available at: http://hjaap.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/HJAAP-2009.pdf#page=68

Ellison, N. B., Steinfeld, C., & Lampe, C. (2011). Connection strategies: Social capital implications of Facebook-enabled communication practices. New Media & Society, 13(6). doi:10.1177/1461444810385389

Fischer, C. S. (1982). To dwell among friends: Personal networks in town and city. Chicago, IL:University of Chicago Press.

Gallegos, T. (2018). Instaman: A Case Study of Male Identity Expression of Instagram. ProQuest. [online] Available at: https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/docview/2169968356?pq-origsite=primo [Accessed 15 May 2019].

Gerlitz, C., & Helmond, A. (2013). The Like economy: Social but- tons and the data-intensive web. New Media & Society, 15.

Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. In T. Gillespie, P. Boczkowski, & K. Foot (Eds.), Media technologies: Essays on communication, materiality, and society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Goffman, E. (1956). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. 2nd ed.

Goffman E. (1971) Relations in public: Microstudies of the public order. London: Penguin.

Goodman, L. (1961). Snowball Sampling. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 32(1). Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2237615

Goodyear, V., Casey, A. and Kirk, D. (2014) Tweet me, message me, like me: using social media to facilitate pedagogical change within an emerging community of practice, Sport, Education and Society, 19:7, 927-943, DOI: 10.1080/13573322.2013.858624

Gotlib, I. and Joormann, J. (2010). Cognition and Depression: Current Status and Future Directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6(1).

Gray, P. (2011). [online] Psychologytoday.com. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/files/attachments/1195/ajp-decline-play-published.pdf [Accessed 21 May 2019]

Griffiths, P., Gossop, M., Powis, B. and Strang, J. (1993) Reaching hidden populations of drug users by privileged access interview- ers: methodological and practical issues, Addiction, vol. 88.

Haidt, J. and Lukianoff, G. (2018). The Coddling of the American Mind - How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas are Setting up a Generation for Failure. [S.l.]: Penguin Books.

Haidt, J. (2018) Jonathan Haidt The Coddling of the American Mind.[video]. YouTube: Real Time with Bill Maher.

Hecht, M, (1993). 2002-A research odyssey: toward the development of a communication theory of identity. Communication Monographs, 60

Herring, S., Hunsinger, J., Klastrup, L. and Allen, M. (2010). Web Content Analysis: Expanding the Paradigm. International Handbook of Internet Research.

Highfield, T. and Leaver, T. (2016). Instagrammatics and digital methods: studying visual social media, from selfies and GIFs to memes and emoji. Communication Research and Practice, 2(1)

Gil de Zúñiga, H., & Valenzuela, S. (2011). The mediating path to a stronger citizenship: Online and offline networks, weak ties, and civic engagement. Communication Research, 38(3). doi:10.1177/0093650210384984

Gil de Zúñiga, H and Barnidge, M and Scherman, A. (2017) Social Media Social Capital, Offline Social Capital, and Citizenship: Exploring Asymmetrical Social Capital Effects, Political Communication, 34:1, DOI: 10.1080/10584609.2016.1227000

Jenkins, R. (2004). Social Identity. New York, NY: Routledge. Doi: 10.4324/9780203463352

Jenkins R. (2010). The 21st century interaction order. In: Hviid Jacobsen M (ed.) The contemporary Goffman. London: Routledge

Joormann J. (2005). Inhibition, rumination, and mood regulation in depression. In Cognitive Limitations in Aging and Psychopathology: Attention, Working Memory, and Executive Functions, ed. RW Engle, G Sedek, U von Hecker, DN McIntosh. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press

Joormann J, Siemer M. (2004). Memory accessibility, mood regulation, and dysphoria: difficulties in repairing sad mood with happy memories? J. Abnorm. Psychol. 113

Joormann J, Siemer M, Gotlib IH. (2007). Mood regulation in depression: differential effects of distraction and recall of happy memories on sad mood. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 116

Jung, E., & Hecht, M. (2004). Elaborating the communication theory of identity: Identity gaps and communication outcomes. Communication Quarterly, 52 (3)

Kertzer, D. (1983). Generation as a Sociological Problem. Annual Review of Sociology, 9(1).

Khalsa, S., McCarthy, K., Sharpless, B., Barrett, M. and Barber, J. (2011). Beliefs about the causes of depression and treatment preferences. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(6).

Krefting, L. (1990). Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45 (3).

Kwon, K. H., Stefanone, M. A., & Barnett, G. A. (2014). Social network influence on online behavioral choices: Exploring group formation on social network sites. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(10). doi:10.1177/-0002764214527092

Lader M. (2015) Generalized Anxiety Disorder. In: Stolerman I.P., Price L.H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Psychopharmacology. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Lareau, A. (2011). Unequal childhoods. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press.

Leitenberg, H. (2013). Handbook of social and evaluation anxiety. Springer.

Lessig, L. (2005). Free culture: The nature and future of creativity. New York: The Penguin Press.

Lessig, L. (2008). Remix - making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Lewycka, S., Clark, T., Peiris-John, R., Fenaughty, J., Bullen, P., Denny, S. and Fleming, T. (2018). Downwards trends in adolescent risk-taking behaviours in New Zealand: Exploring driving forces for change. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 54(6).

Lin, N. (2008). A network theory of social capital. In D. Castiglione, J. W. Van Deth, & G. Wolleb (Eds.), The handbook of social capital. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lin, N. (2001). Social capital: A theory of social structure and action. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Maccoby, E. (1999). The Two Sexes. Belknap Press.

Maher, B (2018) Jonathan Haidt The Coddling of the American Mind. [video] Directed by B. Maher. YouTube: Real Time with Bill Maher.

Malone, K. (2007). The bubble‐wrap generation: children growing up in walled gardens. Environmental Education Research, 13(4).

Meese, J. (2014). “It Belongs to the Internet”: Animal images, attribution norms and the politics of amateur media production. M/C Journal, 17, 2.

Mental Health Foundation. (2016). Fundamental Facts About Mental Health 2016. Mental Health Foundation: London.

Meyrowitz J. (1985). No Sense of Place. New York: Oxford Univ. Press

Meyrowitz J. (1989). The generalized else- where. Crit. Stud. Mass Commun. 6(3)

Meyrowitz J. (1997). Shifting worlds of strangers: medium theory and changes in "them” versus “us.” Soc. Inq. 67(1)

Miller, B. (2015). “Dude, Where’s Your Face?” self-presentation, self-description, and partner preferences on a social networking application for men who have sex with men: A content analysis. Sexuality & Culture. doi:10.1007/s12119-015-9283-4

Miller H. (1995) The presentation of self in electronic life: Goffman on the Internet. Proceedings of the embodied knowledge and virtual space conference, London, http://www.dourish.com/classes/ics234cw04/miller2.pdf

Mossakowski, K. (2014). Mental Illness - Sociology - Oxford Bibliographies - obo. [online] Oxfordbibliographies.com. Available at: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199756384/obo-9780199756384-0087.xml#obo-9780199756384-0087-bibItem-0001 [Accessed 3 Jun. 2019].

Montgomery, S. (2011). Handbook of Generalised Anxiety Disorder. Springer Healthcare Ltd.

Nimh.nih.gov. (2019). NIMH » Suicide. [online] Available at: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml [Accessed 13 May 2019].

Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 109

Noy, C. (2008) Sampling Knowledge: The Hermeneutics of Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11:4, DOI: 10.1080/13645570701401305

Noyes, J., Booth, A., Hannes, K., Harden, A., Harris, J., Lewin, S., Lockwood, C. (2011). Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in cochrane systematic reviews of interventions.Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group, 1. Availabe at: http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance

Nunkoosing, K. (2005). The Problems With Interviews. Qualitative Health Research, 15(5).

O'Keeffe, G. and Clarke-Pearson, K. (2011). The Impact of Social Media on Children, Adolescents, and Families. PEDIATRICS, 127(4).

Ong, E., Ang, R., Ho, J., Lim, J., Goh, D., Lee, C. and Chua, A. (2011). Narcissism, extraversion and adolescents’ self-presentation on Facebook. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(2).

Ons.gov.uk. (2018). Suicides in the UK - Office for National Statistics. [online] Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/suicidesintheunitedkingdom/2017registrations [Accessed 13 May 2019].

Parker, S. in Allen, M. (2017). Sean Parker unloads on Facebook: “God only knows what it's doing to our children's brains”. [online] Axios. Available at: https://www.axios.com/sean-parker-unloads-on-facebook-god-only-knows-what-its-doing-to-our-childrens-brains-1513306792-f855e7b4-4e99-4d60-8d51-2775559c2671.html [Accessed 22 May 2019].

Peterson, J. (2013), Reality and the Sacred. [video] Directed by J. Peterson. Youtube

Pleck, J., Sonenstein, F., Leighton, Ku. (2004). Masculinity ideology and its correlates. Gender Issues in Social Psychology.

Putnam, R. (2015). Our Kids. [S.I.]: Simon & Schuster.

Rainie, L., & Wellmann, B. (2012). Networked: The new social operating system. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Recuero, R., Araujo, R., & Zago, G. (2011, July). How does social capital affect retweets? Proceedings of the fifth International Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence Conference on Weblogs and Social media, Barcelona.

Samaritans. (2018). Suicide facts and figures. [online] Available at: https://www.samaritans.org/scotland/about-samaritans/research-policy/suicide-facts-and-figures/ [Accessed 13 May 2019].

Shah, D., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2008). Social capital. In P. J. Lavrakas (Ed.), Encyclopedia of survey research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Song, H., Zmyslinski-Seelig, A., Kim, J., Drent, A., Victor, A., Omori, K. and Allen, M. (2014). Does Facebook make you lonely?: A meta analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 36.

Sontag, S. (2005). On photography. New York, NY: Rosetta Books.

Speigel, A. (2008). Old-Fashioned Play Builds Serious Skills. [online] Mobile.presskit247.com. Available at: http://mobile.presskit247.com/EDocs/Site578/Old-Fashioned%20Play%20Builds%20Serious%20Skills%20_%20NPR.pdf [Accessed 24 Jun. 2019].

Statista. (2019a). Facebook users worldwide 2018 | Statista. [online] Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/ [Accessed 22 May 2019].

Statista. (2019b). Social network profile creation by gender UK 2010-2017 | Statistic. [online] Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/271892/social-network-profile-creation-in-the-uk-by-gender/ [Accessed 20 May 2019].

Stryker, S., & Burke, P., (2000). The past, present, and future of Identity Theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63 (4)

Thapar, A., Collishaw, S., Pine, D. and Thapar, A. (2012). Depression in adolescence. The Lancet, 379(9820).

Twenge, J. (2017a). Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?. [online] The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/09/has-the-smartphone-destroyed-a-generation/534198/ [Accessed 20 May 2019]

Twenge, J. (2017b). iGen - Why Today's Super-Connected Kids are Growing up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood. New York: Atria Paperback.

Usborne, S. (2017). The U-turn generation: have British teenagers stopped learning to drive?. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/money/shortcuts/2017/jul/11/the-u-turn-generation-have-british-teenagers-stopped-learning-to-drive [Accessed 20 May 2019].

Waling, A. (2016). “We Are So Pumped Full of Shit by the Media”. Men and Masculinities, 20(4).

Walther, J. B., Van Der Heide, B., Kim, S.-Y., Westerman, D., & Tong, S. T. (2008). The role of friends’ appearance and behavior on evaluations of individuals on Facebook: Are we known by the company we keep? Human Communication Research, 34(1), 28–49. doi:10.1111/j. .2007.00312.x

Warburton, S. and Hatzipanagos, S. (2013). Digital Identity and Social Media. Information Science Reference. [online] Available at: https://www.dawsonera.com/readonline/9781466619166 [Accessed 15 May 2019].

Wilson, T. and Fenlon, W. (n.d.). [online] Tomax7.com. Available at: http://www.tomax7.com/mcse/apple/How%20the%20iPhone%20Works.docx [Accessed 22 May 2019].

Wood, H. (2017). How Women Talk: Heather Wood Rudulph Interviews Deborah Tannen - Los Angeles Review of Books. [online] Los Angeles Review of Books. Available at: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/how-women-talk-heather-wood-rudulph-interviews-deborah-tannen/ [Accessed 20 May 2019].

World Health Organization (2018) - Adolescent alcohol-related behaviours: trends and inequalities in the WHO European Region, 2002–2014. World Health Organization. [online] Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/382840/WH15-alcohol-report-eng.pdf [Accessed 20 May 2019].

Wu, Z. and Fang, Y. (2014). Comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders: challenges in diagnosis and assessment. Shangai Archives of Psychiatry, [online] 26(4). Available at: http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/ps/i.do?&id=GALE%7CA421910377&v=2.1&u=ed_itw&it=r&p=AONE&sw=w [Accessed 21 May 2019].

Xinaris, C. (2016). The individual in an ICT world. European Journal Of Communication, 31(1), pp. 58 68. doi:10.1177/0267323115614487

Zhao, S. (2005). The Digital Self: Through the Looking Glass of Telecopresent Others. Symbolic Interaction, 28(3).